Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth. (Genesis 1)

It’s a commonly accepted platitude that we shouldn’t define ourselves by our work. If somebody said this in a social setting, the vast majority of us would smile and nod, without even thinking to challenge it. Unfortunately, it is wrong. The Christian should, in fact, be defined by his work. Work is a fundamental part of our identity.

God commands us to work

What exactly is work? We find the answer in the first command that God gives us: “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion.” (Genesis 1) It is somewhat surprising how concrete this is: bear children and work the earth. We are used to abstract commands like “Love God and your neighbour.” But until our work has sorted out the bottom level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we cannot ascend to higher goals. St Paul, a part-time preacher and part-time tent-maker, confirms that Christians still have this responsibility today: “if any would not work, neither should he eat.” (2 Thessalonians 3) The material work set before us, whatever that may be, is our first responsibility.

Often, we forget that God’s command to work came before the Fall. We think of the responsibility to work as being a way to stave off death, as a consequence of sin and of material corruption. But God’s command comes while we are still living in the Garden of Eden. This is the first thing that God says to us, immediately after we are created! Before we are even capable of dying, God has already asked us to work the earth. God’s vision of the perfect human life includes work.

Work is a cross

Of course, this doesn’t mean that work is perfect. Thanks to our sin, pain is commingled with the joy of our work: with woman’s childbearing comes labour pain; with man’s toil comes sweat.

Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; … And unto Adam he said, … In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return. (Genesis 3)

Despite the difficulties associated with childbearing and work, it is clear that God’s first commandments provide meaning to our lives. Studies reflect this tension between difficulty and meaning. If you poll parents for happiness on a daily basis, then they turn out, on average, to be less happy than non-parents. But if you poll them for life satisfaction, they turn out to be happier!

Work outside of the home, similarly, is difficult, but provides meaning. Many people strive for early retirement, excited to have an empty nest and the whole day free for golfing, thinking this will make them happier. Then it all happens, they find out that it isn’t satisfying, and they have to find something else to do. Every church I’ve been in has been filled with retirees like this - older people who see the parish council as their new source of meaning in life.

We hear that there are some which walk among you disorderly, working not at all, but are busybodies. Now them that are such we command and exhort by our Lord Jesus Christ, that with quietness they work, and eat their own bread. (2 Thessalonians 3)

This is because God has made us for work (including both home-making and bread-winning). I don’t think I need studies to prove to you that work entails difficulties, but studies definitely also show that work provides meaning: working till later in life is associated with better physical health and mental health, if the job is “high quality” and the WHO confirms it too:

Decent work supports good mental health by providing: a livelihood; a sense of confidence, purpose and achievement; an opportunity for positive relationships and inclusion in a community; and a platform for structured routines, among many other benefits.

“No pain, no gain,” as the exercise motto says. The Lord phrases it this way: “If any man will come after me, let him take up his cross daily.” Just like Jesus’s Cross shows us that the gates of heaven were opened through His suffering, so too the gates to a better life are opened through the difficulties of daily work.

But mere difficulty does not, of course, make for good work. Lots of people were crucified, but they didn’t effect the salvation of the human race. Similarly, lots of people have terrible jobs that reduce their life satisfaction. The studies specify that, to increase life satisfaction, the work must be “high quality” or “decent” to contribute to our life satisfaction.

As Christians, I would argue that we are not just looking for work to be “decent,” but, in fact, good. After all, work takes up more of our lives than prayer, than our social lives, than our hobbies, than almost anything except sleep. When St Paul tells us that “Whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God.” (1 Corinthians 10), surely this applies to work as well? Christians’ work must be good enough to be to the glory of God.

So what does that actually look like? God’s first words to mankind, l think, serve as a guide. Here is the text as a quick refresher:

Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth. (Genesis 1)

This places two demands on our work:

(1) Work must fulfil our material needs, and more.

Be fruitful, and multiply.

Our economic activity should be sufficient to be fruitful (a lifetime net contributor to society) and to multiply (to support children). To fulfil God’s command to work, we must be net contributors to society, and we must be able to support a reasonable quality of life for a family. We are required to work and contribute towards this goal in so far as we are able.1 Leeching off of others’ generosity without working is a sin.

Of course, working to support our societies and families also means not working so hard that we cannot support our societies and families. The first command is to be fruitful and multiply, and the work exists to support that good. There is a common misconception that a homemaker’s job is to enable a breadwinner’s career. This is precisely the wrong way around. Work outside of the home is valuable because it supports the home. Similarly, it is not Christian work if it requires so much time or energy that it hurts the worker’s contributions to home life.

It should also be noted that employers and economic systems have a responsibility to breadwinners. As Pius XI wrote, “In the first place, the worker must be paid a wage sufficient to support him and his Family.” (Quadragesimo Anno). A job that does not pay a just living wage is not decent work for a Christian. In fact, injustice to the wage earner is traditionally understood as one of the four “sins that cry to Heaven for vengeance.” Furthermore, stealing from the home life by preventing the worker from fully contributing to it is also a sin.

(2) Work must contribute to a better world.

Replenish the earth, and subdue it:

and have dominion … over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

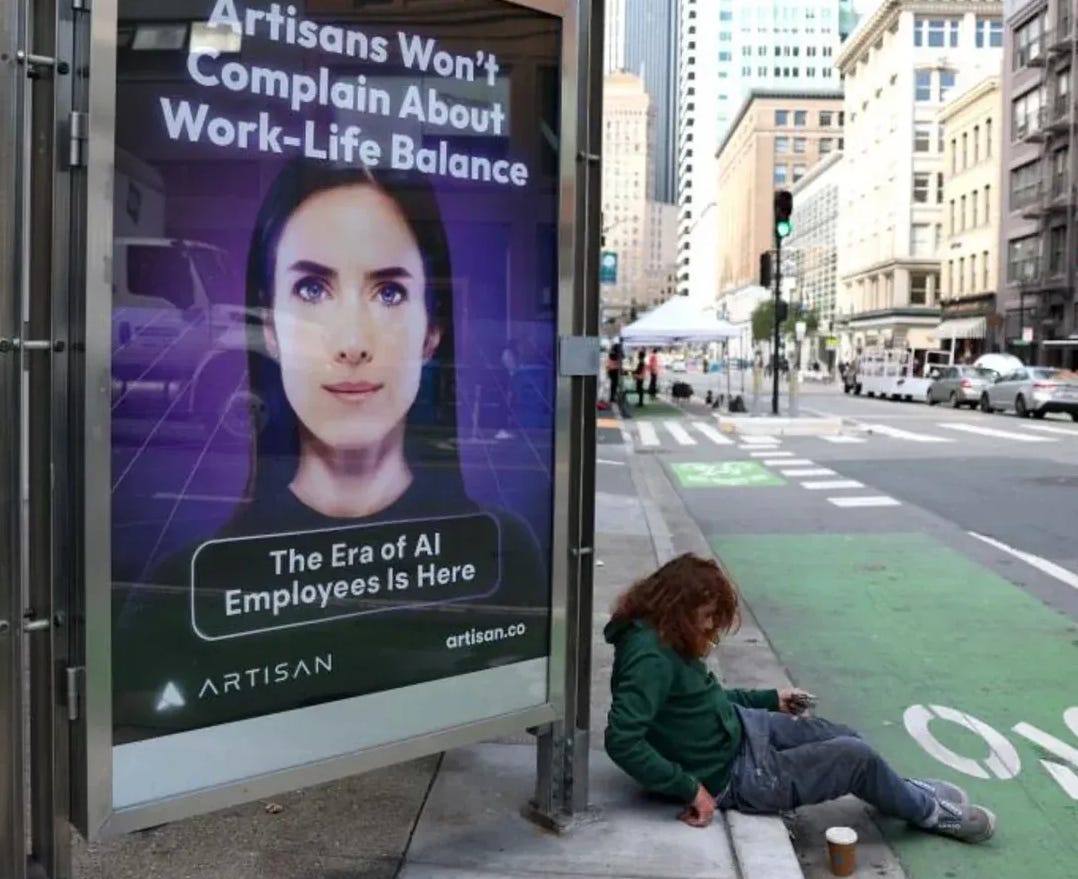

Having dominion over something does not mean to domineer and destroy, replacing what we have been given with our own work. Yet, all too often, our work does this, contributing to and profiting from an unsustainable system. Christian work cannot be complicit in consumerism’s irreversible environmental damage, in a technological development that aims to disconnect us from biology and nature, or in unbridled capitalism’s exploitation of the poor as a resource. This approach is how one builds the second tower of Babylon, and it is doomed to fail. I was recently asked to work on a project that aimed to lay off thousands of healthcare workers and replace them with AI. Christians cannot work jobs that are complicit in creating this kind of a dystopia.

The Christian view of dominion over the world means protecting and ruling over it so as to help it become the best possible version of itself. Pope Francis writes:

According to the biblical account of creation, God placed man and woman in the garden he had created (cf. Gen 2:15) not only to preserve it (“keep”) but also to make it fruitful (“till”). Labourers and craftsmen thus “maintain the fabric of the world”. Developing the created world in a prudent way is the best way of caring for it, as this means that we ourselves become the instrument used by God to bring out the potential which he himself inscribed in things. (Laudato Si’, par. 124)

When our work uses natural resources in a sustainable way to create goods, when it contributes to our family and local society, and when it helps our system to be more just, then we are truly contributing to mankind’s dominion over the world. When we exploit the earth’s natural resources, the animals sharing our earth, and worst of all, other people, to sate our greed, we are not exercising dominion. Consumerist excess invalidates the second half of God’s commandment to work. Our work should make the world look like the Shire, not like Blade Runner.2

We should identify proudly with work

Work is not just a necessity that Christians must deal with. From God’s first commands to us after creation, to St Paul’s advice to Christian communities, to our brain’s requirements for good mental health, we have been called to work, whether this be at home or in the workplace.

It is only through taking up this cross that we can be fruitful, multiply, and have dominion over the earth. When we embrace work as a key part of our identity, we fulfil our vocation as humans. Doing so also reminds us that Christians cannot do just any job, and must work in a way that fulfils God’s commands. Let us, then, daily take up our cross, and be sanctified by it.

I add this qualifier “in so far as we are able,” because not everybody is capable of being an economic net positive. Many disabled people are likely to be a net negative economically throughout their lives. This does not mean that they should starve under St Paul’s maxim “if any would not work, neither should he eat.” (2 Thessalonians 3). If they could work, they would. In fact, their existence is part of the reason that we should strive to be economic net positives - so that, from our surplus, the most disadvantaged are also able to live.

I know, I’ve been spending too much time reading the Lord of the Rings. I wanted to put real places in here, but realised it sounded hopelessly naive. I figured that putting in fictional settings, albeit ones that connect to human society, allows us to draw the comparisons to our own world without getting caught up in details.

That was real food for thought. Thank you.

I have two questions.

You say that we should not exploit the earth because of greed, but how much exploitation is that? How much oil, or coal or gas is too much? If all extraction of minerals is wrong we could have no solar cells and no windmills; won’t we be like the Amish? I’d rather live in the Shire too, so perhaps a good thing, but shivering in the cold is not a future I’d relish, and I don’t think it would make me holier.

The second question is about the intrinsic value of work. I’m a medical doctor in the UK, and medicine here used to define a doctor’s life. Doctors would work extra hours, or get up at night and not infrequently work on past usual retirement age. That attitude has largely vanished in favour of “work/ life balance”; this is a major contributory cause of our NHS crisis. One reason for this (and I’m being very controversial) is that a majority of doctors are now women, and they have competing claims on their time, particularly if they have children. In your view how should a mother portion out her time in terms of “mothering” and work outside the home?

Thanks.